Pruning apple trees is an important pomotechnical measure that may initially seem complicated and difficult. In this article, I want to dispel such myths about pomotechnical practices through a systematic and simplified approach, if they are standardized on the following fundamental principles:

- The duration of pomotechnical work should not exceed 30 seconds per tree for smaller cultivation forms, 60 seconds for medium cultivation forms, and 90 seconds for larger cultivation forms (if we perform pomotechnical work on the tree for longer than the specified time, we are certainly causing damage).

- We perform pomotechnical work on fruit trees at least six times a year.

- In fruit trees, we engage in pomotechnical work at least six times a year.

- Pomotechnical operations are not considered in isolation but as a complex technological process that complements or is complemented by other agrotechnical measures.

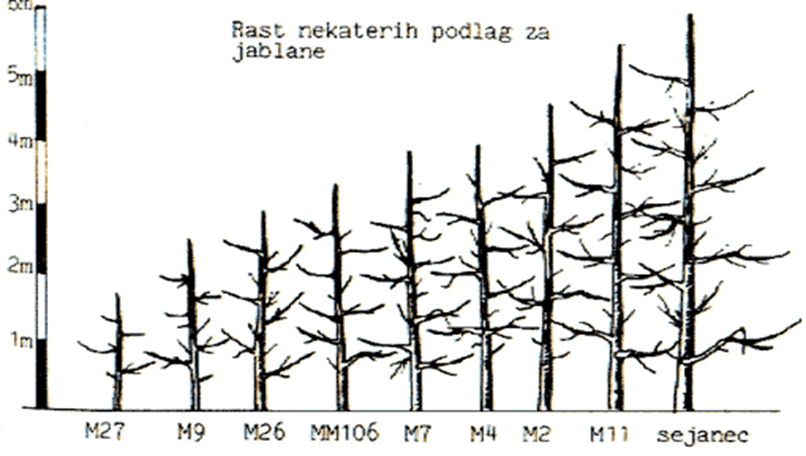

- Continuously follow the latest technological knowledge, which globally aims to achieve a concept of fruit cultivation that allows for easily reachable small trees (using less vigorous apple rootstocks like M-9 and M-27) or even large trees (for use with self-propelled platforms), where minimal manual labor is required (apart from highly productive harvesting of 2,000 kg or more per picker in 8 hours), which must be as straightforward as possible to be carried out by cheaper and less skilled labor.

Fruit trees grafted onto dwarf, less vigorous rootstocks form smaller trees that are simpler to cultivate, prune, and manage with other pomotechnical operations.

2. Establish a minimally standardized monitoring system to track essential data for defining pruning methods and timing, operational techniques and intensity of pruning, and other planned pomotechnical and agrotechnical measures in the new production year. These data include: Growth vigor and health status of trees Bud development and differentiation Pest and disease incidence Fruit set and development Weather conditions affecting growth and fruiting Previous year’s yield and fruit quality

Last year’s yield realization per variety, including the fruit load per tree, fruit quality ratio, average fruit weight, and average dry matter content in the fruit.

- Harvest start and end dates with a meteorological analysis of vegetative temperature thresholds from the last day of harvest to the end of the growing season.

- Post-harvest technology, foliar nutrition strategies, potential use of growth regulators, or autumn pruning techniques.

- Calculate the average trunk diameter at 20 cm height from the grafting point, based on the average of at least 20 measurements per variety.

- Quick own analyses or standardized triennial pedological analyses from November to February on N min

Regularly updated climatological data for absolute minimum temperatures, especially for stone fruit.

3. Education, training, and operational organization of pruning are implemented based on the analysis of the above-mentioned data, ensuring a safe, consistent, and high-quality yield, rather than anxiety due to weather and particularly inadequate technological decisions in the past year, which typically increase the risk of alternate bearing or excessive fruit load.

4. Therefore, pruning fruit trees or the entire set of pomotechnical operations are no longer just old-fashioned knowledge involving ladders, shears, and a pruning saw. They now represent a global approach with standardized procedures aimed at achieving a clearly and simply defined goal: consistently obtaining a high-quality fruit yield each year at the lowest possible production cost (e.g., apples at 0.7 to 0.9 HRK per kg).

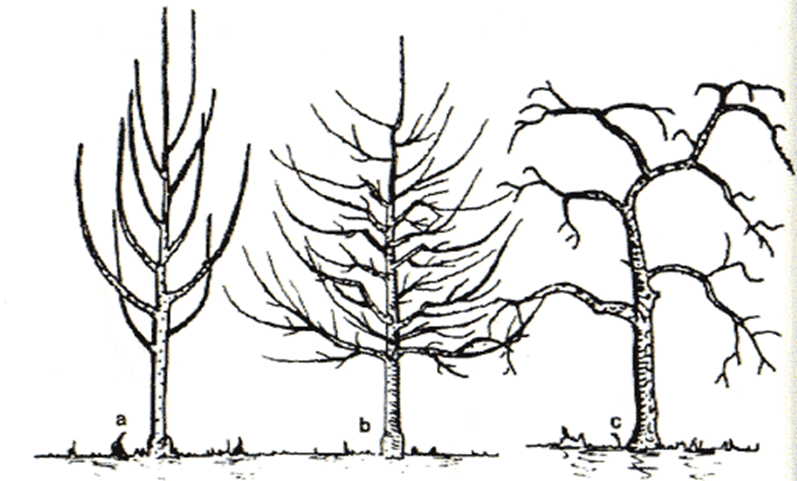

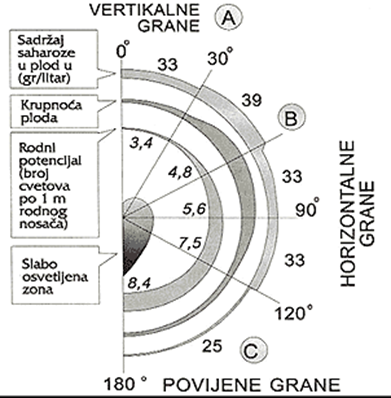

A = Youth (1-3 years), vigorous growth, low fruitfulness, minimal pruning

B = Full bearing (1-25 years), moderate growth, high fruitfulness, moderate to intensive pruning

C = Aging of trees (25-50 years), minimal growth, moderate fruitfulness (alternate bearing), intensive pruning

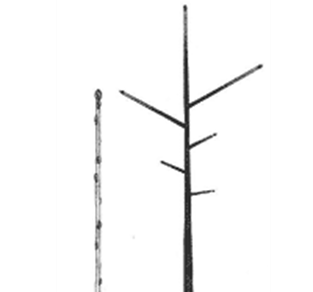

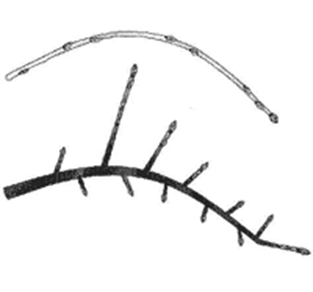

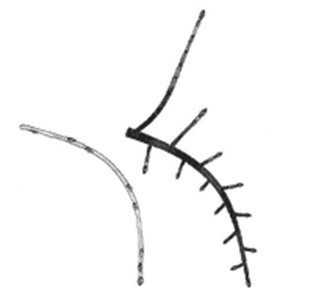

Simplified basic laws of growth and fruitfulness in three positions of a fruit branch.

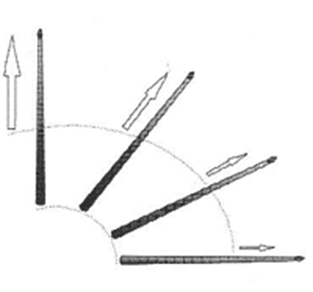

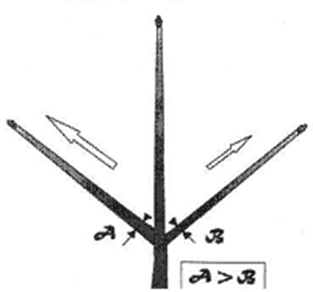

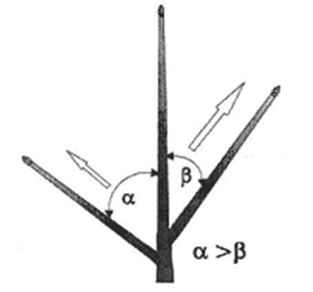

7. Rule: Branches with a wider angle towards the conductor (main trunk or scaffold branch) grow less vigorously than those with a sharper angle.

8 Rule: Vegetative bud break on a one-year-old shoot in a vertical position is always stronger at the top and weaker towards the base of the shoot, where there are fruit buds on medium or short fruiting wood, while fruit buds at the top of such shoots are rarer.

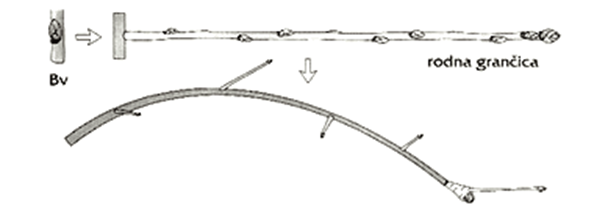

10. Rule: The awakening of vegetative buds depends on their position on a one-year-old shoot in a horizontal position where optimal coverage of the shoot with fruiting buds is expressed on short fruiting wood along almost the entire length of the shoot.

12 Rule: Bud break of vegetative buds depends on their position on a one-year-old bent shoot in a sharp curve where there is significant or even excessive growth of short fruiting wood along the entire length except at the top of the shoot, where typically a longer non-fruiting or replacement shoot grows.

Knowledge of these rules leads to the following conclusions, which every fruit tree pruner must understand to successfully communicate with the tree and achieve optimal production results together: Vertical or steeply angled branches are more vigorous. Two branches of equal thickness at the same height and angle grow equally vigorously. Branches at higher positions grow more vigorously. Branches with larger diameters at the same height grow more vigorously. Branches with more secondary branches exhibit greater vigor. Branches closer to the main trunk or scaffold branch grow more vigorously. Branches with wider angles towards the main trunk grow less vigorously.

- As fruit trees grow more, pruning should be reduced or even omitted, potentially supplemented by techniques such as root pruning or the use of growth retardants (known as growth regulators). In Croatia, the retardant Regalis is registered, which also has positive effects on reducing infection with Erwinia amylovora bacteria.

- The most effective growth control is achieved by using dwarfing rootstocks, grafting height, and planting trees shallower, all expertly designed when establishing orchards.

- The younger and more juvenile the fruit tree, the greater its growth potential; conversely, as the tree ages, its growth potential diminishes.

- Early pruning increases growth potential, while later pruning diminishes it.

- A low fruiting potential increases the growth potential of fruit trees, while moderate to high fruiting potential (with appropriately retained fruit buds) reduces growth potential.

- To correct reduced growth potential, we decrease it with agrotechnical measures (fertilization, irrigation, and inter-row and in-row cultivation), intensive and early pruning, as well as chemical and timely manual fruit thinning.

- To correct increased growth potential, we reduce it with minimal and later pruning, late summer pruning, use of growth retardants, root pruning, and agrotechnical measures such as reduced or omitted fertilization, minimal irrigation, narrower herbicide strips, and less frequent inter-row cultivation.

From all the mentioned points, it globally follows that:

- from all the above, it globally follows that we prune young, low-yielding trees, trees with high growth potential, or trees with low fruiting potential late and minimally but

- for older fruit trees with reduced or minimal growth potential but increased fruiting potential, we prune them appropriately earlier, moderately, or more intensively.

Young trees, trees with high growth potential, or trees with low fruiting potential are pruned late and minimally. Older fruit trees with reduced or minimal growth potential but increased fruiting potential are pruned appropriately earlier, moderately, or more intensively.

Fruit trees have physiologically two developmental stages of buds: vegetative or growth buds, from which depending on the position and conditions of nutrition or climatic factors, a shorter or longer shoot of the current year grows, or only a leaf rosette with a vegetative bud, or the vegetative bud with a leaf rosette directly transforms into a fruiting bud.

Leaf buds in pome fruits

A shoot bud in pome fruits

The development of fruit and a young shoot from a fruiting bud in pome fruits

Differentiation or initiation of flower buds is a complex physiological process. Understanding this process simplifies fruit production for those who grasp it, while it complicates matters for those who do not. The technological goal of a successful fruit grower is to reduce the number of fruiting buds to an optimum level each year, ensuring consistent and high fruit production.

When a grower is filling the necessary production volume of an orchard, as planned in the orchard’s concept, it is important to encourage the growth of current year’s shoots on the existing ideal tree. Once these shoots fill the necessary volume, they must stop growing and start producing assimilates or organic matter required for the so-called differentiation or initiation of flower buds.

One of the many theories of differentiation, and in my opinion, the simplest to understand, is the C

(carbon-nitrogen) theory. In this theory, C represents fruitfulness or assimilates (growth-inhibiting hormones) produced during the completed or moderate growth of fruit trees, while N represents the mineral growth substances (growth hormones) that increase or prolong growth. There are three possible ratios defining the following potential states:

- High C

Ratio: Indicates a state where fruitfulness and production of assimilates are high, leading to more flower bud differentiation.

- Balanced C

Ratio: Reflects a balanced state of growth and fruitfulness, leading to moderate bud differentiation and stable growth.

- Low C

Ratio: Indicates vigorous growth due to high nitrogen levels, leading to fewer flower buds and more vegetative growth.

Understanding and managing these ratios helps in achieving the technological goal of consistent and high fruit production.

- N > C: Excessive growth, which promotes vegetative growth and thus prevents optimal differentiation of fruiting buds.

- N = C: An optimal balance between growth and fruitfulness, which optimizes growth and fruiting, and allows for an optimal fruiting volume and quality differentiation of fruiting buds on all types of branches.

- N < C: Insufficient growth, which excessively increases differentiation of flower buds, thereby indirectly reducing fruiting volume of the tree and increasing the likelihood of alternate bearing in fruit trees.

Differentiation and initiation of fruit buds are thus a continuous process of growth and formation of fruit buds that occurs on current-year, one-year-old, two-year-old, or older branches. Globally, this process spans from the end of flowering, which represents the peak physiological stress for fruit trees (especially during abundant and explosive flowering), until the beginning of the next flowering season.

Using pomotechnics, fertilization, and agrotechnics for fruit trees during the production year, we aim to optimize the N/C ratio, which should be closer to N > C in the first third of the production cycle, closer to N = C in the second third, and somewhere between N = C and N < C in the third third of the production cycle. If we are capable of ensuring optimal conditions for the differentiation of flower buds with our technological knowledge (pomotechnics, fertilization, agrotechnics, and protection of fruit trees from diseases and pests), it is possible even on this year’s shoot, which has achieved optimal length for filling the intended fruiting volume from the beginning of vegetation to the end of the first vegetation period, and in the second vegetation period, with minimal growth and effective assimilation, transitioned into the phase of optimal fruit bud formation or differentiation.

It is naturally much easier and safer to differentiate flower buds on one-year-old, two-year-old, or older wood, as shown in the diagrams below, and for the fruit grower, the quicker one-year differentiation is more desirable.

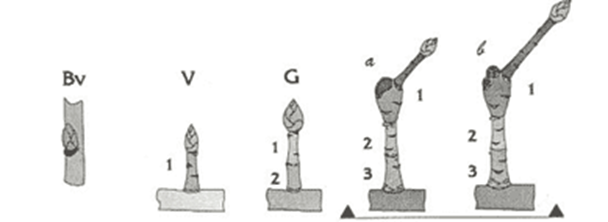

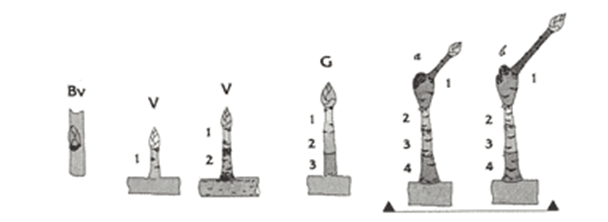

Development of fruiting wood (one-year-old)

Bv = Lateral vegetative (non-fruiting bud)

G = Generative (fruiting bud)

1, 2 = years of growth

a = fruiting spur on which a fruit was formed

b = fruiting spur on which a fruit was not formed

Development of fruiting wood (two-year-old)

Bv = Lateral vegetative (non-fruiting bud)

V = Vegetative (non-fruiting bud) or developing fruiting wood/bud

G = Generative (fruiting bud)

1, 2, 3 = years of growth

a = fruiting spur on which a fruit was formed

b = fruiting spur on which a fruit was not formed

Development of fruiting wood (three-year-old)

Bv = Lateral vegetative (non-fruiting bud)

V = Vegetative (non-fruiting bud) or developing fruiting wood/bud

G = Generative (fruiting bud)

1, 2, 3, 4 = years of growth

a = fruiting spur on which a fruit was formed

b = fruiting spur on which a fruit was not formed

Graphical representation of the formation of fruiting wood on a fruiting twig (this year’s)

Types of branching and fruiting in pome fruit

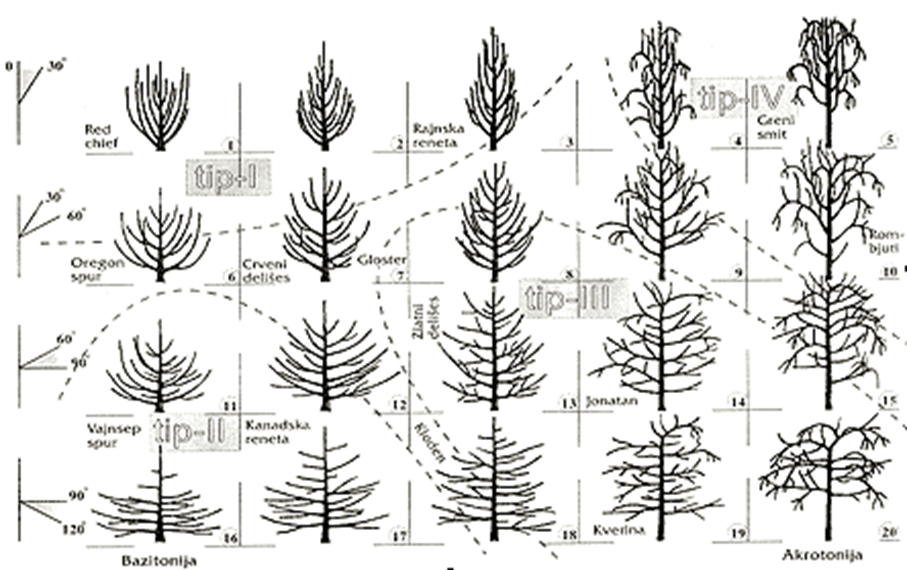

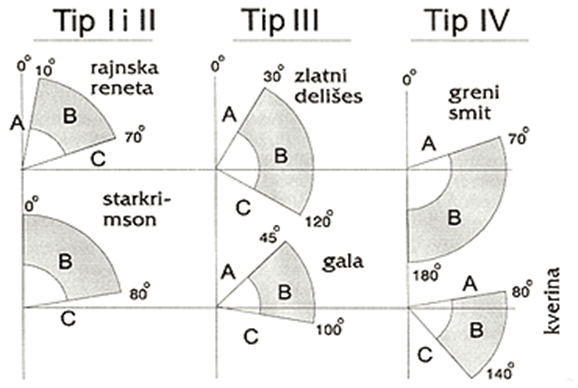

The most widespread continental fruit species is certainly the apple, and it is on this fruit and its pomotechnics that thorough standardization of pomotechnics has been primarily conducted. Different varieties within a single species have different growth patterns or types of branching, which are generally divided into basitonic, mesotonic, and acrotonic. Examples of branching for apple are as follows:

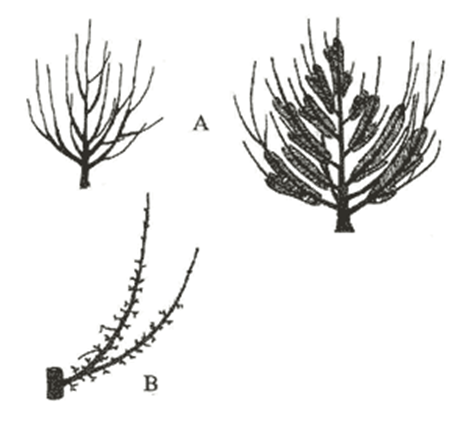

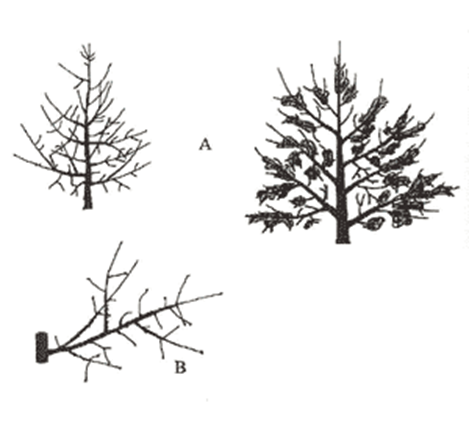

Basitonic type of branching and fruiting

A typical representative of this type of branching is the Starkrimson variety, or more broadly, spur types of various apple varieties, which include current popular varieties of dwarf apple trees. These are trending in organic orchards or processing apple orchards, enabling very dense planting of 10,000 or more trees per hectare and very low production costs.

Varieties with this type of branching, which typically have a sharper angle, differentiate flower buds closer to the base or origin of the branches, and therefore require sharper or so-called short pruning.

This type of fruiting does not enable high or very high yields, and therefore, varieties of this fruiting type are considered less productive varieties.

Basitonic type of branching and fruiting

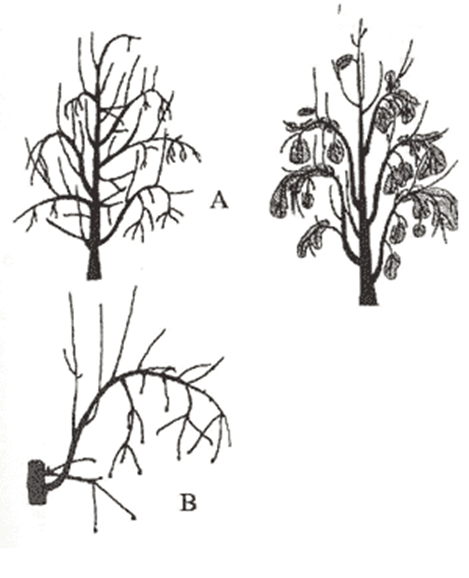

Mesotonic type of branching and fruiting

Varieties of this type of branching independently differentiate most of their flower buds along the middle of the branches, regardless of the branching angle, and therefore require a combination of both long and short pruning. Varieties with a sharper angle of mesotonic branching are considered less productive or moderately productive varieties, while varieties with a wider angle of mesotonic branching are generally more productive or even highly productive varieties.

Renetta type with a sharper angle of mesotonic branching and fruiting

Idared type with a wider angle of mesotonic branching and fruiting

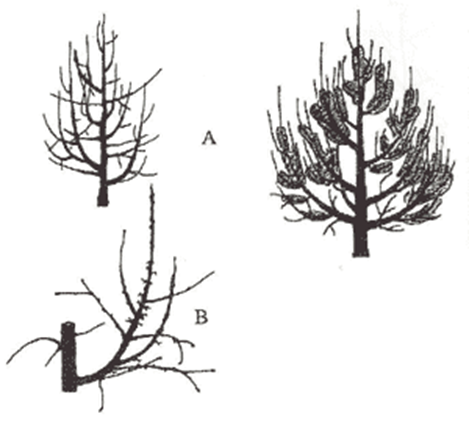

Acrotonic type of branching and fruiting

Ovaj tip grananja obično ima oštriji kut grananja, a tipičan predstavnik je sorta Granny Smith. Sorte ovog tipa grananja karakteriziraju diferenciranje većeg dijela cvjetnih pupova na krajevima grana, neovisno o kutu grananja, te stoga zahtijevaju isključivo dugotrajnu rezidbu.

Zbog produžene diferencijacije cvjetnih pupova tijekom proljeća, preporučuje se kasnija rezidba neposredno prije početka vegetacije za sorte s ovakvim tipom plodonošenja.

Granny Smith acrotonic type of branching and fruiting

Practical application of acquired knowledge about different types of branching and fruiting

Understanding the types of fruiting shown in the diagram below is a fundamental basis for implementing standardized production technology. In the case of pomotechnics methods specific to a fruit species according to variety characteristics, which must be well understood to achieve maximum productivity with a particular variety. This knowledge, combined with the fundamental pruning rules mentioned earlier, the assessed physiological state of the variety in a fruit farming concept, and its specific branching and fruiting characteristics, define the necessary standards for conducting practical operational pomotechnical activities:

- seasons of pruning – pomotechnical works (winter, spring, summer, autumn)

- timing of pruning (early, standard, late)

- intensity of pruning within the season or production year (1/5 = five passes, 1/4 = four passes, 1/3 = three passes, 1/2 = two passes, 1 = one pass)

- methods of pruning – pomotechnical techniques (branch bending, breaking or tearing branches, pruning dominant branches, incising or sawing to encourage growth or fruiting, capping dominant, fruiting, and atrophied branches, releasing competitive branches, long final pruning of basic fruiting branches, short final pruning of basic fruiting branches, use of chemical agents to restrain growth, use of chemical agents for fruit thinning, use of mechanical or physical methods for fruit thinning, manual fruit thinning, root pruning of fruit trees).

Diagram of four main types of branching and fruiting for different apple varieties.

As an example, we will compare the pruning approach for variety 1 (Red Chief) and variety 5 (Granny Smith) from the previous diagram, assuming excellent flowering potential:

- pruning season – winter

- pruning timing: 1 = standard A according to Fl.; 5 = late B-C3 according to Fl.

- pruning intensity: 1 = 1/2; 5 = 1/3 to 1/5

pruning techniques:

1 = (pruning dominant branches, incising or sawing to encourage growth, capping dominant, fruiting, and atrophied branches, releasing competitive branches, short final pruning of basic fruiting branches, use of chemical agents for fruit thinning, manual fruit thinning);

5 = (branch bending, breaking or tearing branches, pruning dominant branches, incising or sawing to encourage growth and fruiting, capping dominant, fruiting, and atrophied branches, releasing competitive branches, long final pruning of basic branches, use of chemical agents to restrain growth, use of chemical agents for fruit thinning, use of mechanical or physical methods for fruit thinning, manual fruit thinning, root pruning of fruit trees).

From the above, it is clear that there is a significant difference in pruning approach between two varieties with the same branching angle but different fruiting types: Red Chief = basitonic, Granny Smith = acrotonic.

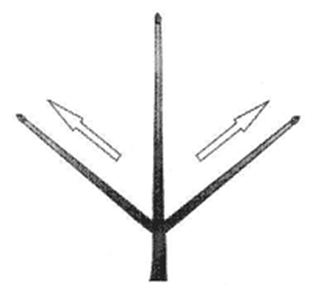

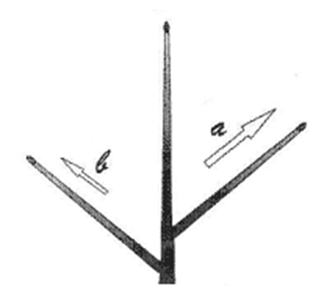

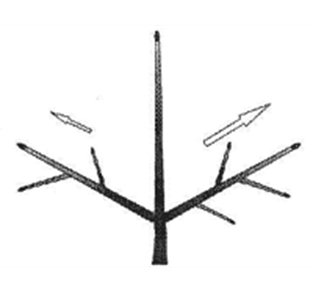

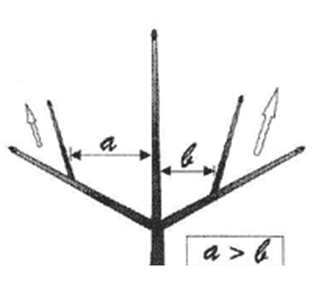

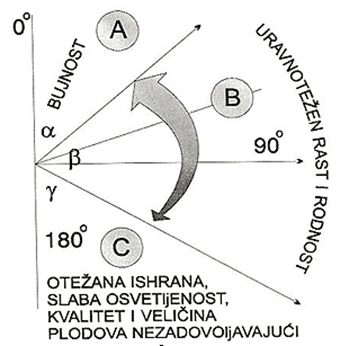

For a better understanding of the importance of branching angle and the correlation between growth and fruiting in different types of fruiting, the following diagrams are significant.

Graphic representation of growth and fruiting zones expressed by branch positioning in space

Graphic representation of the relationship between fruiting potential and fruit quality depending on the different positions of branches relative to the horizontal

Zone of balanced growth and fruiting (B) in different types of fruiting.

How to quickly understand the principles of pruning? Experts can tell you stories, but until you take pruning shears and a saw in your own hands, until you enter the canopy of a tree, you won’t understand anything. It’s like learning to ride a bike: until you hop on it, you won’t learn to ride.

dr. sc. Živko Gatin u Slobodnoj Dalmaciji u prilogu Vrt 24.veljače 2005

SOURCE: vocarstvo.org- written by Franc Kotar